If you’ve ever found it difficult to switch cloud providers or felt limited by your current setup, you’re not alone. Last week, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) released a report (and a short summary) highlighting structural issues in the public cloud market, particularly around limited competition and barriers to customer mobility.

The investigation has been in motion for some time. It began in October 2022, when Ofcom, the UK’s communications regulator, launched a market study to better understand how the cloud sector operates. After hearing from a wide range of businesses, Ofcom identified concerns related to provider dominance and the technical and financial challenges customers face when trying to move between platforms.

Ofcom’s findings were serious enough that in October 2023, they officially handed the case over to the CMA for a full-blown investigation with more legal teeth. Now, after almost two years of digging, the final report is here.

The report was the talk of the industry. It kicked off a huge debate, with AWS and Microsoft immediately pushing back on the findings, while Google called it a “watershed moment”. Beyond the responses from major providers, the report highlights issues that many businesses have experienced firsthand. It marks an important step toward addressing long-standing challenges and encouraging a more open and competitive cloud landscape.

Most of the challenges highlighted in the report, like vendor lock-in and the difficulty of switching, aren’t just business issues; they’re rooted in deep technical limitations. In the sections that follow, we’ll explore how the modern cloud native stack addresses these constraints and offers a more flexible, portable alternative to the status quo.

UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) findings

The CMA’s findings won’t be a surprise if you’ve ever felt stuck with your cloud provider. The problems they found are the same everywhere.

-

Market Concentration: According to the data, the market is basically run by two companies. Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Microsoft Azure control 60-80% of it, which doesn’t leave customers with many real choices.

-

High Barriers to Switching: Customers face significant challenges when attempting to change their primary cloud provider. A recent report revealed that less than 1% of businesses switch annually, not due to satisfaction, but because the process is exceptionally difficult. This difficulty stems primarily from two issues: Egress Fees, which are charges levied for transferring data out of a provider’s cloud, making switching financially prohibitive; and Technical Lock-in, where providers utilize proprietary technologies incompatible with other cloud environments, turning application migration into a substantial obstacle.

-

Restrictive Software Licensing: The investigation also pointed to Microsoft’s software licenses, which can make it more expensive to use essential business software on any cloud other than Azure.

The CMA thinks that because of all this, customers are paying too much and getting less innovation because the big players don’t have to compete very hard. Their main suggestion is to give AWS and Microsoft a special “Strategic Market Status” (SMS) label. This would let the regulator force them to play fairer, for example, by making their services work better with others and stopping unfair pricing.

The catch? It’s going to be slow. The whole process is complicated, so we probably won’t see any real changes for a year and a half, or even more.

Hyperscaler answer to the push for Cloud Sovereignty

This report might be from the UK, but it adds fuel to a fire already burning across the world: the push for cloud sovereignty.

Cloud sovereignty is a simple idea: countries and businesses should have control over their own digital future. It means your data stays under your local laws, safe from foreign access, and you’re not stuck with one provider’s system, particularly when this provider has foreign roots.

The exact problems the CMA found - getting locked in, high fees, and a market run by a few US companies - are why governments are pushing so hard for this. In Europe, new rules like the EU’s Data Act are trying to fix the same things.

In response, hyperscalers like Google, AWS, and Microsoft Azure have launched their own “sovereign cloud” offerings - cloud regions operated in specific countries, often in partnership with local entities, and designed to comply with regional legal and data residency requirements. These offerings aim to reassure governments and enterprises that their data will stay within borders and under local control. However, critics argue that while these solutions check regulatory boxes, they often maintain the same underlying technical dependencies, pricing structures, and vendor lock-in risks that prompted the sovereignty movement in the first place. The core architecture remains centralized, and meaningful autonomy still depends on the level of control truly handed over to local operators. For many, sovereign cloud offerings are a step in the right direction, but not a replacement for deeper infrastructure independence and flexibility.

Sovereign clouds are isolated in their nature. Adopting one is often similar to adopting an entirely new provider, with comparable technical complexity and the same locking-in mechanisms, just under a different brand. For organizations seeking true sovereignty and flexibility, this raises an important question: is replacing one dependency with another really solving the problem, or just reshaping it?

Cloud Native stack as the answer

The cloud native movement emerged as a response to the rigidity and limitations of traditional, monolithic infrastructure. As software systems grew more complex, it became clear that tightly coupled architectures, where applications were bound to specific environments, slowed innovation and increased operational risk. In contrast, cloud native technologies like containers, Kubernetes, and declarative infrastructure made it possible to design applications that are resilient, scalable, and portable from day one.

Over the past decade, this approach has matured into a robust and widely supported ecosystem. Open source foundations like the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) have played a key role, stewarding projects like Prometheus, Envoy, and Kubernetes while fostering a global community of contributors and vendors. Today, the cloud native stack is no longer experimental - it’s the default architecture for companies that value velocity, flexibility, and infrastructure independence.

Crucially, cloud native isn’t tied to any single provider. It’s designed to abstract away the specifics of underlying infrastructure, allowing teams to run the same workloads on any cloud, across regions, or even on-prem. This makes it a powerful counterbalance to the growing dominance of hyperscalers and a natural foundation for building sovereign, interoperable platforms. Rather than being locked into a vendor’s ecosystem or adapting to proprietary “sovereign cloud” offerings, organizations can embrace a stack that puts them in control- technically, operationally, and strategically.

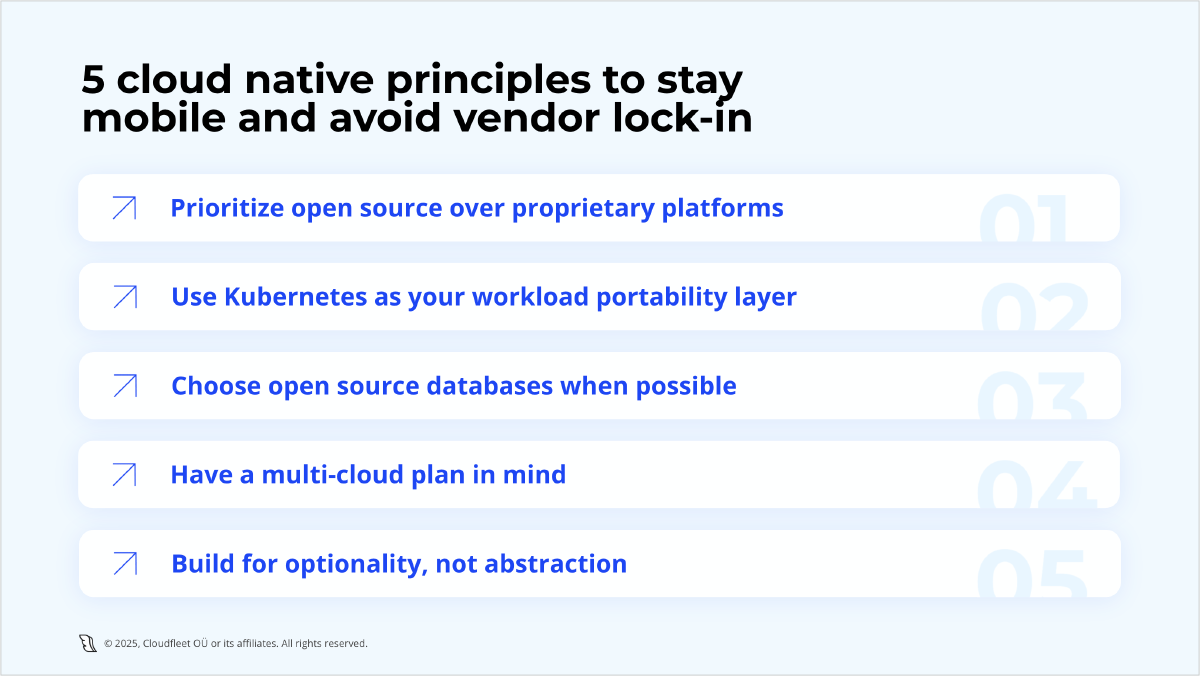

5 cloud native principles to follow if you want to stay mobile and avoid vendor lock-in

If your organization cares about long-term flexibility, cost control, or regulatory resilience, planning for cloud mobility isn’t optional - it’s strategic. The good news is that the cloud native ecosystem offers concrete, proven ways to stay portable while still delivering modern, high-performance infrastructure.

Below are five decisions you can make early to avoid getting locked into a single vendor’s ecosystem.

-

Prioritize open source over proprietary platforms. When selecting core components, like your container runtime, CI/CD system, observability stack, or service mesh, default to open source tools. They have large ecosystems, active communities, and wide support across environments. Open source gives you leverage: you’re not tied to one company’s roadmap, pricing, or availability zone.

-

Use Kubernetes as your workload portability layer. All major cloud providers offer managed Kubernetes (like EKS, GKE, AKS), and they all run upstream Kubernetes under the hood. By building on Kubernetes, you gain the ability to move workloads between providers, or run them in parallel, without rewriting your applications. Just be cautious: managed services often add vendor-specific integrations that can subtly reduce your portability.

-

Choose open source databases when possible. Cloud-native databases like PostgreSQL, MySQL, or even distributed systems like CockroachDB or Vitess can be self-hosted or used as managed services and later migrated if needed. In contrast, proprietary cloud databases (like Aurora or Cosmos DB) offer strong performance but at the cost of long-term lock-in. Pick open protocols and engines to keep your exit options open.

-

Have a multi-cloud plan in mind, even if you don’t start there. Most companies eventually end up using multiple cloud providers; according to CNCF’s 2023 report, organizations were already running workloads across an average of 2.8 unique clouds. Whether driven by compliance, resilience, or strategic reasons, multi-cloud adds complexity that requires preparation. Even if you’re not multi-cloud today, building with a plan for governance, policy enforcement, and orchestration will prevent painful rewrites and fragmented architecture later.

-

Build for optionality, not abstraction. Avoid the trap of over-abstracting everything to chase portability. Instead, make intentional choices that give you options: use standard APIs, avoid proprietary SDKs, and document your deployment architecture clearly. This way, even if you start with a managed service, you’ll have a clear path to self-hosting or switching providers later.

By making these choices early, you avoid building technical debt that limits your strategic freedom. Cloud native gives you the tools, but it’s your architecture and governance that will determine how free you really are.

The future of cloud is flexible, sovereign, and everywhere

The CMA’s report confirms what many teams already knew: the cloud market has become too centralized, and too many businesses are paying the price in the form of lock-in, high costs, and limited control. While regulators are starting to act, the technology landscape has already moved ahead, giving companies the tools to take control now.

The future of cloud isn’t confined to one provider, one region, or even one model. On-prem is making a quiet but meaningful comeback, not as a rejection of cloud, but as part of a more flexible, hybrid strategy. With modern orchestration, Kubernetes-based platforms, and open source tooling, running across multiple clouds and on-prem environments is no longer just a compliance-driven necessity - it’s a practical way to optimize for cost, performance, and autonomy.

Cloud native technologies are the foundation for this shift. They give you the portability, automation, and ecosystem support to build infrastructure that adapts to your needs, not the other way around. The future of cloud is not just public or private, but portable, composable, and built on your own terms. You don’t need to wait for regulation to catch up. The tools to build a more open, sovereign future are already in your hands.